Recently I was asked why pumpfoil wings are actually so wide. When starting sideways from a dock or float, a foil with a large span can sometimes be tricky. Especially if you have no way to position the wing tips underneath the dock or float, a big and confident jump is required when pushing off sideways — something that can feel a bit intimidating for beginners.

To get to the root cuase why many manufacturers produce wings with a larger span — so‑called high‑aspect‑ratio foils — we need to take a short detour into fluid dynamics.

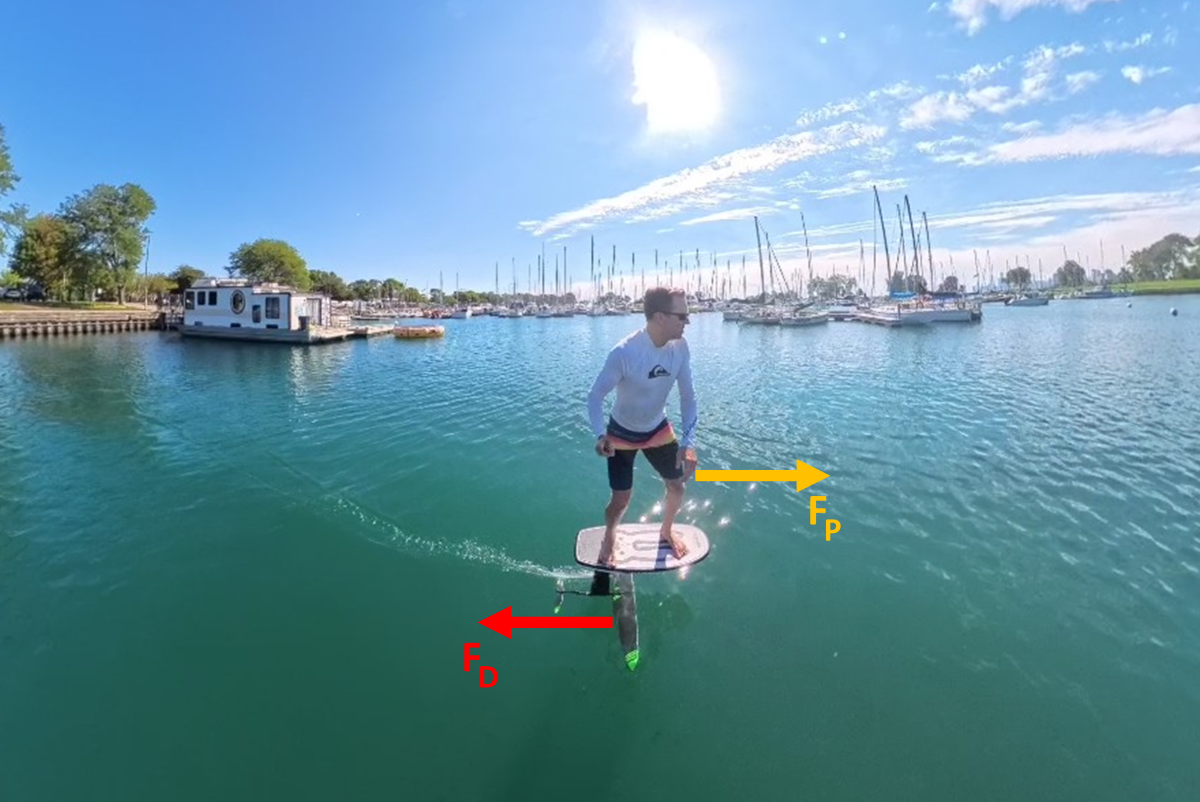

Lift- and propulsion force

First and foremost, the front wing’s job is to generate lift (see also: Physics of a Hydrofoil). Lift is a function of the foils’s shape and the speed at which it moves through the water. In pumpfoiling, the rider must provide the propulsion respectively the necessary speed. The force acting against that forward motion is the drag produced by the foil moving through the water.

Figure 1: Propulsion- and dragforce

That means that the more drag a foil produces, the more energy the pumpfoiler has to put into the system while pumping. Conversely, the less drag a foil has, the less force the rider needs — allowing for longer pumping distances. But what does this have to do with the aspect ratio?

Aspect ratio

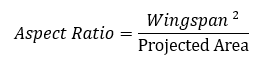

The aspect ratio is the ratio between a wings’s span and its chord length. The wingspan is the distance between the outer wing tips. The chord length is the distance between the leading and trailing edge of the wing. The aspect ratio is calculated by dividing the square of the wingspan by the reference wing area (see also: Dimensions of a hydrofoil).

However, the aspect ratio is not just a number — it has a direct influence on the drag, more precisely on the induced drag of the foil. What we can state is that the ratio of lift to drag increases as the aspect ratio becomes larger. The reason for this lies in the wingtip vortices that form at the edges of the wing.

Wingtip Vortices

Wingtip vortices form primarily at the ends of the wing due to the large pressure differences between the upper and lower surfaces. This pressure difference causes a lateral flow of air, which then rolls up into spiraling, counter‑rotating vortices.

Figure 2: Vortex

Wings with a high aspect ratio have the advantage that the wing tips have less surface area, which reduces the vortex‑induced downwash — and therefore significantly lowers induced drag.

As mentioned earlier, the primary task of the wing is to generate lift. The amount of lift produced depends on the wing’s speed, the density of the water, the wing’s surface area, and the lift coefficient. The lift coefficient itself depends on the wing’s shape and therefore varies between different wing designs.

If we simplify the model and treat speed, water density, and the lift coefficient as constant, then lift depends only on the wing’s surface area. This required area can be achieved through different wing shapes — either with a relatively narrow wingspan and a longer chord length, or with a larger wingspan and a shorter chord length, meaning a higher aspect ratio.

Conclusion

To reduce the induced drag caused by wingtip vortices, designers create wings with shorter chord lengths. As a consequence, the wings need a larger span to achieve the surface area required for generating lift.

However, reduced induced drag is only one component. Wings with different aspect ratios come with different advantages and disadvantages. High‑aspect‑ratio wings are characterized, among other things, by the following features:

- Less drag: more efficient for pumping and allows for longer glides

- Wider speed range

- More stability: the larger wingspan provides greater roll stability

- Slower acceleration and a higher stall speed Less agility

Practical example

As mentioned earlier, wings with a high aspect ratio require less energy to pump forward. This is particularly beneficial for riders who enjoy pumping long distances. And this is not just theory — the current endurance pumpfoil records clearly demonstrate it. At the time this article was written, the endurance record stood at 4 hours with a total pumped distance of 54.8 km. The wing used, the Indiana Condor XL, has an aspect ratio of 12 with a wingspan of 1696 mm.

Winglets

For the sake of completeness, it should also be mentioned that adjusting the aspect ratio is not the only way to reduce the induced drag created by wingtip vortices. Winglets or sharklets, commonly seen on airplane wings, can also reduce the formation of these vortices. They act as a barrier that prevents high‑pressure air from flowing from beneath the wing up around the tip into the low‑pressure area above. In the foiling world, this is seen far less frequently. However, some manufacturers have offered such wings at times. For example, Indiana once had an entry‑level wing for pump‑ and wing‑foiling, the 1100P model, which featured winglets.

Figure 3: Indiana 1100P Complete Setup

Of course, there are many other factors that play a role in wing design. We will not go into these in detail here.

We hope this overview has helped bring a bit more clarity to why high‑aspect‑ratio wings are so common in pumpfoiling, and why they’re a great choice for riders who prefer a foil with strong gliding performance. Whether you’re riding a high‑aspect‑ratio foil or any other model, we wish you great pumping at all times!